Legal precedents and other crude examples abound across the world showing how powerful kings lived in the past, particularly in France, unrestrained by legal constraints. It is rumoured that King Louis XIV, while addressing his Parliament about 400 years ago, told them in no uncertain terms that he was the state, and the state was him, as captured in the French phrase: L’État, c’est moi.

In such a setting, the power of the state came from the king, making him the ultimate source of authority. Of course, the French masses eventually rejected this position of unchecked monarchy. Many who opposed it were hanged, especially those who dared to claim a position above the law.

Meanwhile, in other parts of Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom—a similar situation was brewing. King James I also relieved his Chief Justice of duty because the judge had refused to accept the king’s assertion that he was above the law.

The controversy between King James and his Chief Justice, Sir Edward Coke, arose from a legal debate in which the king asked whether he, as the king, was superior to the law. Without hesitation, since there was nothing really to debate, Sir Edward informed the king, “My Lord, you are high, but the law is higher than you.” This response greatly irritated King James, who promptly sacked the Chief Justice.

What is strikingly surprising is that other members of the judiciary agreed with the king’s view—that he was above the law. These “yes-men” were then appointed to replace the outgoing Chief Justice. Indeed, bootlickers are everywhere, they exist in Africa, in Uganda, and even in Bugisu.

In Uganda, power comes from the people, as clearly stated in Article 1 of the 1995 Constitution. No king, cultural or otherwise is above the law. The nearest person who could be estimated as living above the law on an ad hoc basis is the President, whose civil and criminal liability is suspended while in office.

Articles 98(4) and 98(5) of the Constitution restrain courts of law from entertaining civil or criminal cases against a sitting President. However, the Rwandan Constitution takes a different approach when it comes to presidential immunity.

In Rwanda, the Constitution allows for the trial of a President while still in office, but prohibits prosecution after leaving office for certain offences. Anyone wishing to bring a case against a sitting Rwandan President must do so while the President is still in office.

To encapsulate, Article 114 of the Rwandan Constitution, Exemption from Prosecution of a Former President of the Republic, states that a former President cannot be prosecuted for treason or serious violations of the Constitution, if no legal proceedings for those offences were initiated while they were still in office.

What led to the conflict, and eventual dismissal, of Chief Justice Sir Edward Coke in the United Kingdom was the king’s interference with judicial independence. King James believed he had the authority to meddle in the courts, but the Chief Justice boldly told him otherwise.

In Uganda, the law particularly Article 128(1) guarantees the independence of the judiciary. All authorities are prohibited from interfering with the court’s operations. The judiciary is described as the Un commanded commander, it gives commands but cannot be commanded by anyone.

Article 128 of the Constitution openly guarantees judicial independence, stating that no person or authority can coerce or influence the courts in the execution of their duties.

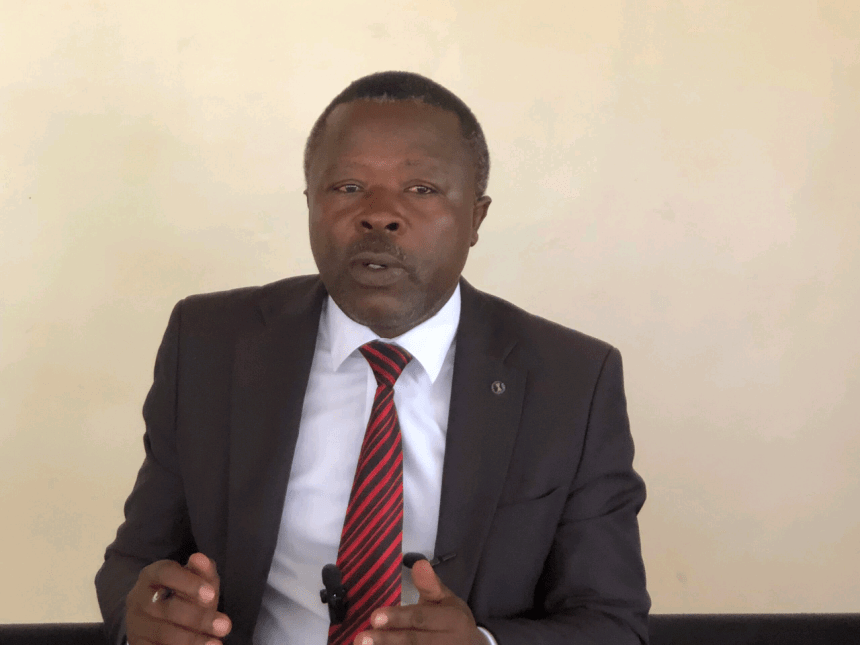

The writer is a lawyer and spokesperson of the Bugisu Cultural Institution.

Tel: 0782-231577