Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) Jane Frances Abodo has decided to ditch the “idle and disorderly” charges that were recently wielded against anti-corruption protestors. This decision came only after significant public and legal pressure, suggesting that sometimes, even the highest legal offices in Uganda need a little nudge from the masses.

DPP Abodo took the stage in Kampala, where she likened her legal decision to a housekeeper cleaning out old junk. According to her, the “idle and disorderly” charge was as outdated as a 1970s disco outfit. She explained, “Our inherited laws are like that old matoke recipe that’s never updated; it’s time to clean up the Penal Code Act. As the President said, no one should be called idle in their own country.”

The decision to drop these charges was portrayed as an administrative move rather than a legal concession. Abodo hinted at a need for laws to be in sync with current realities—almost as if Uganda’s legal system needed a software update. “We can’t keep applying ancient laws like we’re stuck in a time warp,” she added. “We’ve cleared the ‘idle and disorderly’ charges but kept the ‘common nuisance’ for good measure.”

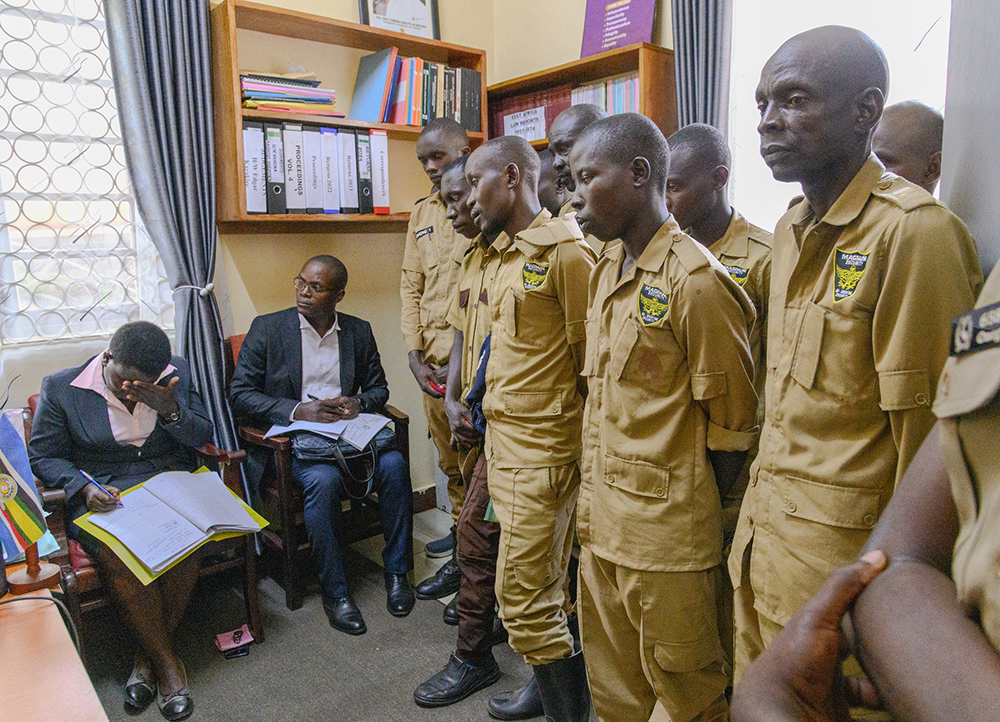

Just last month, over 100 energetic youths found themselves in hot water after they decided to march to Parliament, protesting against corruption. They were swiftly charged with being “idle and disorderly”—a charge as archaic as trying to drive a car with a horse-and-cart license. Their court appearances were like scenes from a historical drama, with Buganda Road, Nakawa, and City Hall courts all hosting this legal theater.

The backlash was swift and stinging. Legal experts, including the esteemed professors from Makerere University, raised eyebrows over the use of colonial-era charges for what seemed like a peaceful march. This criticism was as loud as a boda boda horn in Kampala traffic.

DPP Abodo took the opportunity to throw some shade at Parliament, accusing them of failing to clean up outdated laws. She argued that her office was unfairly criticized for using laws that Parliament had yet to repeal. “It’s like asking a chef to cook with rotten ingredients because the kitchen hasn’t been restocked,” she said. “We are stuck with these laws until Parliament decides to do its job.”

Mr. Chris Obore, Parliament’s communication chief, responded by stating that Parliament follows a strict procedure for repealing laws. “We don’t just wake up and scrap laws,” he said. “We have a process, much like how you can’t just change the menu at a wedding halfway through.”

Human rights lawyer Nicholas Opiyo weighed in, emphasizing that the DPP’s role is to act independently of political pressure. He suggested that the DPP must safeguard this independence, starting with how she handles her office’s duties. “Independence is key, much like how a referee must stay neutral in a football match,” Opiyo explained.

Fellow human rights lawyer Eron Kiiza added a touch of irony, noting that Abodo’s sudden realization of the outdated nature of the charges came rather late. “It’s like finally discovering that your phone has been outdated for years—better late than never, but the damage is done,” Kiiza said.

In a nutshell, Uganda’s legal landscape is now witnessing a peculiar drama—a blend of historical hangovers and contemporary demands. The legal system, much like a well-worn pair of shoes, might need a thorough cleaning and an upgrade. Until then, Ugandans will continue to navigate this legal labyrinth, where the past and present often collide in unexpected ways.